Catherine Cook-Cottone, Ph.D.

Central to each of the Eating Disorders (EDs) is an individual’s relationship to his or her body. That is, the fundamental organizing feature is a disturbance in how the body is experienced, fed, cared for, and accepted. Research has documented a complex etiological course that includes genetic, physiological, familial, and relational influences (Cook-Cottone, 2015a). Central, for many, is the loss of an embodied sense of self (Cook-Cottone, 2015b). Accordingly, along with the other risk factors it is believed that our way of being in today’s culture can lead to risk, and for some disorder. In today’s technological, social media, and image-focused culture, it can be easy to simply ignore, discount, or minimize the importance of the mind and body connection. Through daily implicit an explicit choices, we are all at-risk for travelling down an objectifying pathway upon which an attuned mind and body connection can be lost. Once we are on this path, engagement with the body occurs within the framework of its role in the creation of a manufactured image, edited, and engineered to appear attractive according to current ideals (e.g., thinness, leanness, or with Kardashian/Nicki Minaj curves). Within the unremitting flow of social media “likes”, edits, posts, the casual flips through fashion magazine pages, and hours viewing video screens filled with edited and stylized productions, our sense of who we are as embodied beings fades from awareness. Our individual and perhaps collective consciousness shifts. The body and its corporal needs are split apart from the conceptual image of self so many of us are working to manage. Nevertheless, no matter how far we go down the constructed, idealized image path, the body demands to be fed, exercised, nurtured, and integrated into daily life. In this divide, lies the problem and a big part of the answer.

The split between actual needs and an idealized, manufactured image can become impossible to effectively negotiate. The Attuned Representational Model of Self (ARMS) provides a model for how to get back to a centered, functional, and embodied experience of the self. It is a road map for awareness and self-care (Cook-Cottone, 2015a, 2015b). Attunement and self-care are viewed as forms of self-love. In essence, the ARMS process reflects the caring for oneself in an active practice of loving-kindness. Notably, this shift toward personal ownership of self-care and body appreciation is not new as an approach to eating disorders. You are encouraged to read Kim Chernin’s influential work on eating disorders detailed in, “The Hungry Self: Women, Eating and Identity,” and “The Woman Who Gave Birth to her Mother: Tales of Transformation in Women’s Lives” (Chernin, 1985; 1998). You will see that finding a positive path to recovery that integrates the whole self and involves active self-care has been a long time coming.

Attuned Representational of Model of Self (ARMS)

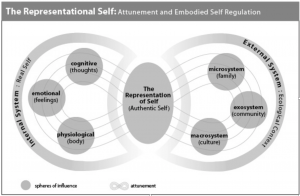

According to the ARMS (see Figure 1), the self is an active construction, a representation of the needs and relational dynamics of the inner and outer aspects of living (Cook-Cottone, 2006, 2015a, 2015b). The inner aspects of self include the physiological (i.e., body), the emotional, (i.e., the feeling), and the cognitive (i.e., thinking) domains. The outer aspects of self include the microsystem (i.e., family and close friends), exosystem (i.e., community), and macrosystem (i.e., culture). How individuals perceive and experience their bodies involves an ongoing interaction among the aspects of self (Cook-Cottone, 2015b; Wood-Barcalow et al., 2010). The two self-systems (i.e., internal and external) are interconnected by attunement and self-care (Cook-Cottone, 2006). Based on Daniel Siegel’s work in the field of interpersonal neurobiology, attunement is defined as a reciprocal process of mutual influence and co-regulation (Siegel, 1999, 2007). The active construction of the self in shown in the center. (See Figure 1) It is the embodiment of the ongoing behavioral patterns that create and maintain attunement within an individual’s inner and outer lives (Cook-Cottone, 2015a, 2015b). As illustrated by the ARMs, effective functioning of the self goes beyond self as subject or object (Cook-Cottone, 2015b). Healthy, embodied self-regulation occurs when an individual is able to maintain an awareness and maintenance of the needs of the inner aspects of self (i.e., physiological, emotional, and cognitive), while engaging effectively within the context of family, community, and culture (see Cook-Cottone, 2006, 2015a, 2015b; Seligman, 2011). See Cook-Cottone (2006, 2015a; 2015b) for detailed explanations of the internal and external influences that lead to and maintain eating disorders.

Figure 1: The Attuned Representational Model of Self.

Adapted from Cook-Cottone, 2006, 2015a, 2015b

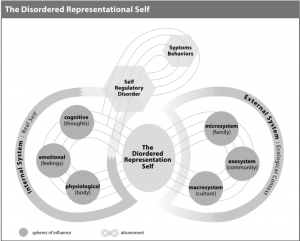

In the case of eating disorder risk, influences from the internal system (i.e., cognitive, emotional, and physiological) and/or the external system (i.e., family, community, or culture) individual, collectively, and/or cumulatively contribute to misattunement and self-care, which fails to develop or is disrupted (e.g., Marcus & Levine, 2004; Cook-Cottone, 2006, 2015a, 2015b). In deference to external pressures and ideals, those at risk may objectify, invalidate, or see the internal aspects of the authentic, inner self as unacceptable (Cook-Cottone, 2006, 2015a, 2015b; Tylka & Augustus-Horvath, 2011). When missattunement, objectification, and invalidation occur, the authentic, inner self is often abandoned or ignored (Reindl, 2002; Tiggemann & Williams 2012). The disordered representational self is constructed to regain, at least affectedly, the individual’s attunement with his or her external, ecological context (Cook-Cottone, 2006; Cook-Cottone, 2015a, 2015b; Reindl, 2002; Tiggemann & Williams 2012; See Figure 2: The Disordered Representational Self). The internal aspects of self (i.e., thoughts, feelings, and physiological needs) are left without representation through action or voice (Chernin, 1985; Cook-Cottone 2015a). Eating disordered behaviors, thoughts, and motivations take on a critical role in the organization and functioning of the self. The internal aspects of self become attuned to the experience of eating disorder symptoms in a self-perpetuating, self-reinforcing disorder (Cook-Cottone, 2006). As a tangible symbol of the self, the body becomes something to control, change, and bring into alignment with cultural or media ideals. In chronic, clinical cases, the eating disorder becomes the central organizing feature of the individual’s life, his or her identity (e.g., Arnold, 2004; Cook-Cottone, 2006; Cook-Cottone, 2015a, 2015b; Reindl, 2002).

Figure 2: The Disordered Representational Self.Adapted from Cook-Cottone, 2006, 2015a, 2015b

A Solutogenic Approach to Eating Disorders

Taking a salutogenic approach, patients can work on their symptoms, relationships, and coping, as well as strive toward a life that positive psychologists would describe as flourishing (Cook-Cottone, 2015b; Keys, 2007; Seligman, 2011; Tylka, 2012). Full recovery, or flourishing, is viewed as an awareness of, and commitment to, an attuned inner and outer life in which internal needs are met and the external demands are negotiated without compromise to physical or mental health (Cook-Cottone, 2006, 2015a, 2015b; Keys, 2007; Seligman, 2011). For many years, treatment providers have appropriately focused on the physical, cognitive behavioral, and familial aspects of treatment. These approaches often include body image work to reduce body dissatisfaction and distorted body image (see Cash, 2008). From the solutogenic perspective, future directions in ED treatments can build on current treatment models that focus on reducing symptoms and move toward the possibility of creating a positive, healthy, and thriving relationship with the body (Cook-Cottone, 2015b).

Distinctly, the ARMS approach holds that those struggling with disordered eating can hope for a recovery that is more than a battle to avoid symptoms and tolerate, or ignore, what they perceive as their less-than-perfect bodies (Antonovsky, 1978; Cook-Cottone, 2015b; Frisen & Holmqvist, 2010; Seligman, 2011; Wood-Barclow, Tylka, & Augustus-Horvath, 2010). As an augmentation to traditional therapeutic goals, individuals with EDs can work to nurture a healthy relationship with the body through the development of positive body image and an active practice of self-care (Cook-Cottone 2015b). Further, there is no to need to wait until eating and body-related symptoms have remediated, as safe, positive practices, embracing a positive body image and self-care can begin during any phase of treatment. For more on the framework for a salutogenic approach to flourishing and well-being, see Keys (2007) and Seligman (2011).

What is Positive Body Image?

According to the experts, positive body image features: inner positivity, body appreciation, body acceptance and love, a broad conceptualization of beauty, and active filtering of information in a body protective manner, and respect for the body (see Avalos, Tylka, & Wood-Barcalow, 2005; Tylka, 2012; Wood-Barcalow et al., 2010). A growing field of research has shown that positive body image is distinct from body dissatisfaction and is uniquely associated with well-being (Avalos et al., 2005; Tylka, 2012; Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015). It is important to acknowledge that to those who are struggling with eating disorders and a strong, negative body image, the idea of a positive body image can seem unrealistically ambitious (Cook-Cottone, 2015b). The gap between what the patient is feeling in the current moment and where the therapist would like them to be can feel too large. Patients need to have an embodied experience of a winnable gap. It is critical to follow a process that allows positive body image to be experienced as accessible and possible. That is, the process must be broken down into small, actionable steps. Further, given the medical risk inherent in eating disorder symptoms, it is important to focus on body image within the context of supporting a patient’s ability to self-regulate, address life-threatening eating disordered behaviors, and increase effectiveness within his or her relationships and environment (Cook-Cottone, 2015b).

Growing toward a healthy embodied self involves active engagement that goes beyond rather than thinking about the body differently (Cook-Cottone, 2015b). As first explicated in the article, “Incorporating Positive Body Image into the Treatment of Eating Disorders: A Model for Attunement and Mindful Self-Care,” moving a patient toward flourishing is a two-step process (Cook-Cottone, 2015b). Flourishing requires both awareness and action. That is, the flourishing inherent in positive body image necessitates the embodiment of two ways of being: (a) having an awareness of the internal and external aspects of self, and (b) engaging in mindful self-care (Cook-Cottone, 2015b). Mindful self-care behaviors bring awareness and commitment to action and attitude matters. Within the context of mindful self-care, patients attend to the needs of the self with loving-kindness (Cook-Cottone, 2015a). For patients in recovery, this requires a shift from negative, judgmental, over concern with the body toward a stance of loving self-care that honors the inherent need for mind and body connection. In this way, recovery is filled with self-compassion and an appreciation for the living, breathing, functioning physical self (Cook-Cottone, 2006, 2015a, 2015b; Keys, 2007; Tylka, 2012; Tylka, Russell, & Neal, 2015). In the ARMS method, patients are coached to use self-care tools to both protect the self from stress and unhealthy external standards and demands, as well as to assess and choose environmental conditions that enhance well-being and intentionally engage in health promoting behaviors (e.g., intuitive eating, exercise, and yoga; Cook-Cottone et al., 2013; Cook-Cottone, 2015a, 2015b).

From Eating Disorder to Flourishing: Embodiment of Attunement and Self-Care

It is important to reinforce engagement in sound treatment that includes a team with training and experience treating individuals with eating disorders (i.e., a medical doctor, nutritionist, and mental health professional; Cook-Cottone 2105b) and that the patient is receiving the appropriate level of care (i.e., outpatient, day treatment, or inpatient care). By adding the ARMS approach, there are several practices that can help cultivate an inner and outer attunement that facilitates an appreciation and care for the body, as well as supports the body’s role in the environment (i.e., functions). These self-care tools bolster inner strength and promote resilience (Cook-Cottone, 2015b). The 10 practices are listed here as a short review. For an extended discussion with empirical support for each practice see Cook-Cottone (2015b).

Practice #1: Body Acceptance

Body acceptance and love involves a comfort with the body exactly as it is (Frisén & Holmqvist, 2010; Tylka, 2012). It involves an attunement of the inner aspects of self (i.e., thought, feelings, and body) via cultivation of a cognitive schema for the body that accepts all shapes, sizes, and unique qualities, as well as an emotional valance of loving-kindness toward the body (Cook-Cottone, 2015b). In this way of viewing the body, it is understood that no one can be perfect and that pursuit of this “illusory ideal” can be physically and mentally harmful (Tylka, 2012, p. 659; Wood-Barcalow et al., 2010). For a wonderful “in treatment” approach use Thomas Cash’s (2008) book, The Body Image Workbook: An Eight-Step Program for Learning to Like Your Looks. The text begins with a set of assessments that can help bring patients to an awareness of their body image challenges.

Practice #2: Body Appreciation

Body appreciation is the practice of gratitude for the function, health, and aspects of the body (Tylka, 2012: Frisen & Holmqvist, 2010; Wood-Barcalow et al., 2010). Reflecting attunement between the body and its role in the environment, the body is valued for its inherent strengths and its ability to function within the environment rather than its appearance (Frisen & Holmqvist, 2010). This includes thinking about and focusing on the body, and noticing and praising the body for what it is able to do rather than critiquing its appearance (e.g., “My arms are so strong;” Tylka, 2012; Tylka & Augustus-Horvath 2011). At the cognitive and emotional levels, there is an appreciation of all shapes and sizes, ethnicities, skins tones, types and shades of hair, skin art, scars, mobility, disability, and genetic differences (Cook-Cottone, 2015b).

Practice #3: Self-Compassion

According to Neff (2003), self-compassion is the practice of responding to challenges and personal threats by treating oneself with nonjudgmental understanding and kindness, acknowledging distress, and realizing that pain and struggle are part of the universal human experience. Helping create attunement among the inner aspects of self, self-compassion practice involves a cognitive reframing of challenge and threat as well as an emotional shift toward loving-kindness rather than frustration or fear. Self-compassion has been found to buffer the associations from media-thinness related pressure to disordered eating and thin ideal internalization (see Tylka, Russell, & Neal, 2015).

Practice #4: Spirituality

Spirituality can play a substantial role in positive body image. It is theorized that those with positive body image hold a belief that there is a higher power, or an order in the universe, that accepts them unconditionally (Tylka, 2012). Spirituality integrates each of the internal aspects of self (i.e., the thinking, feeling, and physical) through passionately held beliefs and active practices (Cook-Cottone, 2015b). The body is seen as a temple for the spiritual self that must be maintained and cared for in order for an individual’s spiritual life to flourish (Tylka, 2012).

Practice #5: Addressing Basic Physical Needs

In contrast to making choices based on appearance or unrealistic external ideals or standards, health promoting self-care behaviors support positive body image (Wood-Barcalow et al., 2010). This involves listening to the body’s needs and choosing behaviors based on the needs of the body (Cook-Cottone, 2015b). These practices help to bolster a connection with the inner aspects of self and include addressing basic physical needs (i.e., medical care, nutrition, and hydration), exercise for health and enjoyment, and adaptive methods for stress relief and body care (Cook-Cottone, 2015b).

Practice #6: Intuitive Eating

In early to middle recovery, intuitive eating may be more aspirational as the patient works to adhere to meal plans and reconnect with his or her body (Cook-Cottone, 2015b). Clinically, a meal plan offers the patient safety and security from the possible indecision and ambiguity that can be associated with intuitive eating (Cook-Cottone, 2015b). Intuitive eating can be presented as a possibility once those with EDs are able to detect their hunger and satiety cues (Tribole & Resch, 2012). It is important to know that there, quite possibly, can be a time when eating is enjoyable, connected to the body’s needs and wants, and involves a trust in the body for knowing what it needs.

Practice #7: Healthy Exercise

Research has emerged that suggests that exercise for health and enjoyment may be associated with positive body image (Frisen & Holmqvist, 2010). For example, adolescents with high levels of body satisfaction tend to view exercise as a natural and important part of life, as joyful, and health promoting (Frisen & Holmqvist, 2010). How one exercises matters. It is important to note individuals with positive body image do not tend to describe exercise as a way to lose weight or control the size or shape of the body and that they slow down or rest when they need to (Wood-Barcalow et al., 2010). Further, having health-related, rather than appearance-focused reasons for exercise may be protective (Homan & Tylka, 2014; O’Hara, Cox, & Amorose, 2014) and help. Calogero and Pedrotty (2004) found that mindful exercise improved outcomes for those with AN. Yogic approaches may be especially beneficial for those with eating disorders (e.g., Carei, Fyfe-Johnson, Beuner, & Brown, 2010; Cook-Cottone, 2015a; Cook-Cottone, Beck, & Kane, 2008; Klein & Cook-Cottone, 2013).

Practice #8: Appreciating the Function of the Body

Appreciating the body for its functions rather than its appearance can be protective (Cook-Cottone & Phelps, 2003). Physical self-esteem, or feeling good about what your body can accomplish is inversely related to body dissatisfaction, or being dissatisfied with the size and shape of your body (Cook-Cottone & Phelps, 2003).

Practice #9: Actively Filter Messages

The ability to filter messages from others and the media in a body protective manner may be associated with maintenance of a positive body image (Tylka, 2012; Wood-Barcalow et al., 2010). Those with a positive body image seem to have a cognitive filter that screens information to determine if it is accepted or rejected (Tylka, 2012; Wood-Barcalow et al., 2010). Information that is assessed as negative or harmful to body image is rejected (e.g., weight-related comments; photo-shopped or idealized images of beauty, femininity, and masculinity). According to Tylka (2012), this process includes the affirmation that filtering information in this way creates more time and energy to focus on the important aspects of life.

Practice #10: Body Positive Friends

Those who have a positive body image secure and maintain relationships with individuals who unconditionally accept their bodies and the bodies of others and do not hold an idealized version of the body as important (Cook-Cottone, 2015b). Specifically, those with a positive body image maintain friendships with others who are accepting of themselves (Wood-Barcalow et al., 2010). Within the context of these relationships, an individual feels valued and loved based on his or her inner qualities such as creativity, personality, and intellect (Tylka, 2012). Further, in body positive relationships, appearance is not frequently mentioned (Frisen & Holmqvist, 2010). If appearance is mentioned, it is related to the creative, interchangeable aspects (e.g., clothes, jewelry, or hairstyle; Tylka, 2012).

Conclusions

Cultivating mental health goes beyond ameliorating symptoms and asks for more than languishing (Keys, 2007; Seligman, 2011). For those struggling with eating disorders, flourishing and well-being should be considered as possibilities (Cook-Cottone, 2015b). This includes engaging in mind and body attunement and effective, mindful self-care while negotiating environmental demands and supports. The ARMS approach posits that positive body image can play a powerful role in the treatment of eating disorders as patients go beyond traditional therapeutic goals to nurture a healthy relationship with the body and others (Cook-Cottone, 2015b). Through awareness and active practice, patients recovering from eating disorders can potentially experience positive body image along with mental and physical health. They can flourish.

For more on positive body image and self-care see the full article in Cook-Cottone, (2015b). Further, see Mindfulness and Yoga for Self-Regulation: A Primer for Mental Health Professionals (Cook-Cottone, 2015a) for a detailed description of the Mindful Self-Care Scale.