Laura Eickman, Psy.D. and Carmen Cool, MA, LPC

INTRODUCTION

“Young people are not the problem – they are part of the solution. Youth are not only our future but our present, and we will not solve any pressing social problems without their active, creative participation and leadership.” – Allan Creighton & Paul Kivel

Teenagers can be powerful and influential players in the work of transforming cultural attitudes and beliefs about weight, health, and body image.

In fact, we believe that young people have the passion and ability to change the world. When teens are able to redirect the massive amounts of energy they expend on trying to change their bodies, and instead use their time and talents to make positive social change, they are an unstoppable force in their communities. Young people are trustworthy, brilliant, and wise – and their wisdom deserves to be heard.

Both of us have worked in the eating disorder treatment field. We have been through body hatred and eating disorders and have come out the other side. As therapists, our work 1:1 with people in our offices was important and fulfilling. We also felt drawn to work at the cultural level and to do something about the conditions that were, in part, bringing people into our offices in the first place. There are many ways to work at the cultural change level. Education, policy, outreach – but the one we felt the most called to was facilitating the process of young people doing prevention work in their own schools.

We can share with you our numbers: how many presentations were given, the number of youth reached, the percentage of youth who gained valuable leadership skills, etc. And that is important. But, as is consistent with our message, just as the numbers on the scale do not determine our worth, numbers also do not tell the story of the power of this work, or the depth of the impact that being an advocate has on young lives.

Consider the long-term impact of a young woman who invests her energy into her deepest dreams, rather than in trying to fit herself into the current beauty trends. Imagine the long-term impact of a middle school student who hears a high school leader talk about the ways she’s learning to love herself. Imagine the long-term impact of a generation of young leaders who are confident in themselves, trust their deepest voice, and know that they are effective agents of change.

This is the core of our message and what we help youth to do: redirect their energy to the things that have meaning in their lives. Highlighting the work from the voices and perspectives of teens, this article will explore how we engage young people, the ways in which activism can be a powerful tool for teens to use their voice and find their power, the impact that comes from youth taking the lead in prevention work, and ways that as adults, we can support them in carrying a message of liberation into their communities.

Background

We have worked for 18 years collectively, standing shoulder-to-shoulder with teenagers who want to create a shift in the meanings our society gives to a body size. Deeply rooted in socio-cultural, feminist, social justice, and Health At Every Size® approaches, we developed peer leadership programs in high schools, partnering with them to initiate a cultural shift in the attitudes young people have toward their bodies. We supported powerful teen role models who would take a stand for positive body image for youth of all shapes and sizes, and work to stop weight stigma and body bullying in their schools.

Carmen founded the non-profit Boulder Youth Body Alliance, a youth-driven, peer leadership program established to prevent harmful eating and exercise behaviors, as well as appearance-related harassment, by training high school youth to become leaders in their schools and communities. Through participation in Boulder Youth Body Alliance, youth developed their leadership skills, enhanced their critical thinking skills, taught younger students, and engaged in activism to create change socially, politically, and personally. After nine years of running as a nonprofit, the organizational entity came to a close. However, the work and program is undergoing its next iteration and will be coming back in the fall of 2015.

Laura founded the nonprofit REbeL, a student-driven, peer education program designed to address body image issues and disordered eating. REbeL focuses on training and empowering youth to become peer educators and activists. These students are educated on topics including the prevalence of eating and body image issues, the inefficacy of diets, the impact of negative self-talk, and media literacy. Over the course of a year, students become the educators and initiators (with the guidance of adult mentors). Using a dissonance-based approach, REbeL members lead the way in developing innovative solutions to the body image concerns facing so many individuals today. Through this process, they also move toward healthier relationships with food and their own bodies.

Positive Youth Development

Positive Youth Development is an intentional, pro-social approach that engages youth within their communities, schools, organizations, peer groups, and families in a manner that is productive and constructive; recognizes, utilizes, and enhances youths’ strengths; and promotes positive outcomes for young people by providing opportunities, fostering positive relationships and furnishing the support needed to build on their leadership strengths. (Positive Youth Development, 2014)

Positive Youth Development involves youth as active agents. Young people are so ready to move from passive recipients of cultural messages about their bodies to active advocates who can create change. They just need adult allies who will invest in them. Start from a place of respect for young people’s autonomy, opinions, desires, and actual capacity to take part in and lead powerful social movements.

Adults may set the structure, but youth are not just the recipients of services. Youth are valued and are encouraged to bring their assets to the table. Adults and youth work in partnership – which means showing up as another messy, complex, human being on the journey. Adults have the power in this world, and in this work we let youth take the lead and we actively work to dismantle the system of adultism.

It’s not about forcing a mission upon us, but allowing us to find it for ourselves. We’re told – “do this, eat this, go here”, so instead of being told “this is our mission”, this time we were given information and then we could say “oh this is what I think is a problem and how I want to approach it.”

As much as possible, our programs were co-created, with youth participating in every aspect of the program, from mission development, to youth positions on the board, to research and evaluation.

IN THEIR WORDS:

When asked about the impact of co-creating these programs, teens said:

We look up to you but you treat us as equals.

It’s so refreshing when adults ask you questions and then genuinely want to know the answer.

When we have ideas, not only was she supportive but she worked to make them happen and bring them to fruition. It showed she actually thought they were good ideas and she actually valued our thoughts and it was a mutual respect. We respected her, she respected us and it made us all feel empowered.

Even though she has done so much work in this field, it didn’t feel like she was “the expert” and we were the kids. She asked for, listened to, and implemented our ideas. And even better, she cared, she hugged, she hung out. She believed in us.

Benefits of partnering with youth

“Young people are often key actors in powerful social movements that transform the course of human history. Yet today, youth are often framed in the mass media as, at best, apathetic, disengaged, and removed from civic action. …we have much to learn from young people who are already engaged in mobilizing their peers, families, and communities towards positive social transformation.” (Costanza-Chock, 2012)

Young people are part of the solution towards preventing eating disorders. Eating disorder prevention and awareness campaigns focused on young people lose potential potency if they don’t involve them in the development of those campaigns. As adults, we can’t define what the youth experience is, and teens are the ones who can speak in ways that their peers can hear. Additionally, young people are more likely to hear messages, and change their attitudes and behaviors, if they believe the message is coming from someone similar to them who face the same pressures.(Sloane and Zimmer, 1993)

Often, contributions that young people make are trivialized. Beyond their youthful energy lies authentic power that comes when we engage them fully in creating messages and campaigns. There are many advantages to partnering with youth. By welcoming and actively seeking their ideas and input, we make sure that messages are relevant to their real, lived experiences.

Other benefits, beautifully outlined by Advocates for Youth (Klindera & Menderweld, 2001) include:

- Fresh ideas, unshackled by the way things have always been done

- New perspectives on decision making, including more relevant information about young people’s needs and interests

- Candid responses about existing services

- Additional data for analysis and planning that may be available only to youth

- More effective outreach that provides important information peer to peer

- Additional human resources as youth and adults share responsibility

- Greater acceptance of messages, services, and decisions because youth were involved in shaping them

- Increased synergy from partnering youth’s energy and enthusiasm with adults’ professional skills and experience

- Enhanced credibility of the organization to both youth and advocates

From our experiences, we know that teens are passionate, rebellious, and hungry for a way to make a difference in the world. After taking eight trips with a group of teens to Washington, D.C. to lobby with the Eating Disorders Coalition for Research Policy and Action, I learned that if you want to make a difference in policy or on Capitol Hill – take teenagers! They are incredibly influential. As adults, we can talk in a public health meeting about the impact of weighing kids in schools – but when they do it, it’s an entirely different conversation and harder to ignore. If you’re going to talk about policies that affect the well-being of young people, they need to be included in the conversation.

There have been benefits to both of us personally, as well.

Carmen: The benefits of partnering with youth have been immense. I have learned how to model my vulnerability while holding my seat. I’ve learned how to ask powerful questions and then step back and watch and cheer and support and applaud. I’ve learned how to intuit what door to knock on so they can open up to their own potential.

It’s as simple and as challenging as opening my heart, showing up as my whole self and genuinely loving them. And that is both a feeling, and a verb. They demand my authenticity, and feel relieved by my vulnerability.

It’s my job to come to them as authentic and humble and fierce as I can be – showing up as my full self, allow myself to be taught by, and moved by, our interactions. My life continues to be changed by the gift of working directly with young people who are so committed to embracing their true selves and making the world a better place. They keep me honest, they call forth my real, human self, they make me laugh, and they give me hope.

Laura: While I have had many training experiences for which I’m very thankful, none has had such a significant impact on me as my work with teens. Their bravery and courage blows me away. These young people, in the midst of the challenges of middle and high school, put themselves out there and push against the status quo. They allow themselves to be vulnerable and advocate for the better world they envision. I cannot imagine having done this work as a teenager; yet they do it every day. They dare to make a difference and in doing so, have opened my eyes to just how much power we all have. Prior to working with these teens, I had never seen Margaret Mead’s famous quote in action–but can “a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens change the world”? Absolutely.

Teens are hungry for adults to treat them as equals, to ask for their input, and honor their opinions. They welcome honesty and appreciate vulnerability. So often I find that the teens I’ve met just want me to “be real.” Graduate school taught me to be a “blank slate” with my clients. Teens taught me that authenticity is much more important. I am a better therapist, teacher, activist, and advocate because of these young people. And I can only wish for others that they have the same opportunity to be swept up by their potential and hopefulness.

Community

Another facet of this work is the way a new community is formed – one in which self-love becomes the norm. One of the recurring findings throughout literature on health and healing is the power of our relationships and connections with each other.

It starts with improving the connection with ourselves and our body, knowing our wants, needs, and feelings. We learn how to choose our integrity over someone else’s approval. These relationships and connections – of a young person and their body, of teens with each other, of teens and adults – were the actual mechanisms that allowed change and growth to happen. There is value in holding classes and workshops; but we found that the ongoing nature of our work allowed deeper relationships and a profound sense of community and connection. Meeting together weekly for 8 months, we engaged in many “reflective conversations” (Siegel, 2014) and “relational dialogue” (Levine & Smolak, 2006), got to know each other deeply, became part of each other’s lives, and have remained there throughout the years.

IN THEIR WORDS

Community can be incredibly healing in its own right, as evidenced by these teens’ statements:

We all love and trust each other so much that, if you are having that voice in your head really strongly – sometimes there’s nothing you can say to it, sometimes you can’t come back out on your own – having this many people that you can literally just talk to and they’ll know exactly what you’re talking about, and know exactly what to say. Having those people is really amazing, and really helps you to come back to yourself.

The biggest thing for me in continuing to move away from disordered eating was surrounding myself with others in the group. When we go out to eat together, I was in a community of people who understood and why it’s important. We all supported each other and had each other’s back around it.

We created a space where it was safe to talk positively about our bodies. A lot of the time in our high school communities, people are so bonded over talking negatively about our bodies and we’re afraid of being called conceited if we differ from that. Together, we learned that we could embrace self love and learn strategies to bring that into our everyday communities.

Activism

“Ask ‘What’s possible?’ not ‘What’s wrong?’ Keep asking.” (Wheatley, 2009, p.145)

The magnificent rebellious energy of teenagers is immeasurably fun to work with and highly effective, especially when it is related to them claiming their truth, rather than rebelling for its own sake. For example, teen smoking can be seen as a rebellious act. Efforts to curb teen smoking by giving medical information and scare tactics had no impact in the numbers of teens who smoked. But teaching them that adult business owners were making money off of manipulating them into smoking–that did work. Then not smoking became an act of rebellion.

Similarly, when young people understand that dieting is an act of conforming, then eating intuitively becomes an act of rebellion. And when they see that appearance standards are externally driven and artificial (and often used by advertisers to manipulate purchasing decisions), then rebelling can look like a critical evaluation of media messages and a rejection of that ideal.

Working with my body allows me power in myself. No one else has control – I’m the one who knows what I need.

As Dan Siegel says, we can “support the adolescent’s need for pushing back on the adult status quo and the exploration of new possibilities.” (Siegel, 2014, p.81)

It’s about changing the norm. The norm is to talk negatively about your body; that’s what everybody does. If that’s how a conversation is going with friends, a lot of people just jump in sometimes. I think that if you’re brave enough to take that step to try to change the norm…to do something where you’re talking positively about yourself – that can be accepted and the norm. It should be; that’s the way it should be.

Youth in REbeL have worked to change this norm through our signature whiteboard photos. This activity asks individuals to publically “rebel” against the normative cultural practice of self-criticism (especially in terms of appearance), and to instead, publicly celebrate a personal quality or characteristic. Participants complete the sentence, “I love my…” and are encouraged to write something that is personal and challenges their comfort level (E.G. “I love my thighs”, “I love my laugh lines”). Afterward, participants engage in group discussions and the photos are displayed in a public area (E.G. busy school hallway, mall entrance, social media sites). Whiteboard photo stations are periodically set up during school lunch, at sporting events and other extracurricular school activities, and in the community.

Harnessing the anger and rebellion that characterizes adolescence in the service of ending discrimination propels youth leaders into action. Involving youth in activism and advocacy around the social forces that contribute to body dissatisfaction and eating disorders can be important tools for prevention, recovery, and heightened psychological well-being (Musick & Wilson, 2008, Stice & Shaw, 2004, Tartakovsky, 2012).

It’s about taking a stand – and becoming the stand. When we do this, it’s not an issue that is apart from us. Who we are is the stand.

Youth from Boulder Youth Body Alliance went to the park after talking about this together. The kids loved the idea of embodying their stand, reflected on what they wanted to be a stand for, and took to the sidewalks.

(Photo credits: Tara Polly Photography)

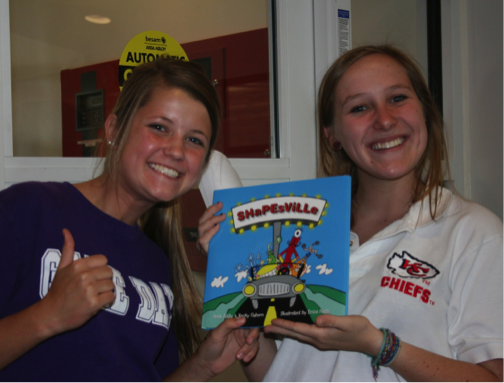

Living the activism in their own lives was demonstrated in the ways they developed and delivered presentations in their communities. This was impactful both to those in the audience, and for the youth themselves. Of course, they learned public speaking skills and how to facilitate conversations, but the biggest impact was the ways it reinforced the message to themselves, over and over. Also of benefit was the mentoring aspect involved in presenting to younger children. When high school students talk about body positivity to those in middle school, or when they read a book like Shapesville to elementary school children, both groups are significantly affected. The younger students look up to and want to emulate the older students, while the teens are able to speak the messages and then model them in a very public way–this enhances their adherence to the messages and promotes further internalization as well.

“We’ve learned through teaching. As I started speaking to other people, I think that was the most effective way to synthesize it into my own life.”

It is that aspect of activism that helped many teen leaders in their own healing process, whether that was recovery from an eating disorder or healing a negative body image.

Other forms of activism that our peer leaders engaged in were: lobbying in Washington, DC, presenting to the School Board, staff and faculty trainings, and outreach of all kinds both in their schools and the wider community. As a result, Congressional Representatives signed on to support eating disorder legislation, the School District added appearance-related teasing to its anti-harassment policy, different conversations began taking place and peers were connected to professional support when needed. Here are some photos of their activism efforts in action:

Jim Knapp Photography

IN THEIR WORDS

When asked what the benefits of engaging activism were to them, teens replied:

It’s given me a purpose and a direction, given me something to be really excited about. To work for something and see it happen – it makes me feel powerful.

The time and energy that a high school student spends thinking about, worrying about, or critiquing his or her body could be put toward something much more meaningful. I have found that cause for myself, and it has completely changed who I am.

This organization has helped me see the beauty in the world; look at my peers with different eyes. It has helped me eliminate those “snap judgments” everyone is so prone to make. Even more importantly, it has helped me with my own self confidence. Now, when I look into the mirror, I don’t automatically look for my faults and how to fix them. I instead notice the little things that make me “me.” It has made me realize that I don’t have to look like anything or anyone else, that my health is much more important than my size, and that I am so much more than a number.

It gave me the push I needed to take the next step in my recovery. It showed me there was another option. If it hadn’t been for that, I am not sure where I would be, or how I would be doing today.

I learned that I have a voice and speaking in front of peers, adults, and Congress has made me realize that my words have power.

I went from having a mindset that I had nothing important to say and nothing to contribute to the world, to thinking I am capable of anything.

Paul Kivel says that to help young people, we don’t need to help them raise their self-esteem, we need to help them experience their power. Obviously, supporting and facilitating teens’ activism efforts does just that.

Online Activism

Teens aged 13-17 spend an average of 4 hours and 4 minutes online daily–more than any other age group. In addition to texting, social media sites are their primary methods of communicating; and not only do they use these to interact, but also to craft their image and influence others. Never before have individuals had this much power right at their fingertips. Unfortunately, this power can often be misused. From the dangerous pull of pro-ana sites to “fitspiration” posts on Pinterest to the horrible stories of teens being mercilessly bullied on Twitter, we are all aware of examples of social media causing harm. However, what would happen if we harnessed teens’ natural desire to socialize, their energy, and creativity, and channeled that in a positive direction on social media?

Youth have traditionally been shut out of many social change movements because adults often dominate the discourse. However, the advent of social media has opened the door for teens to participate in activism in powerful and effective ways. We can educate and motivate teens to use social media “for good.” In fact, there are already many instances of youth leading the way in innovating social movement media practices–from Kony 2012 to the “I am Trayvon Martin” campaign to the song Clouds which has raised nearly 1 million dollars for osteosarcoma research. Far from being disengaged, self-centered, or apathetic (as teens are often described), these young people WANT to “do good.” They want to be heard and valued and respected.

Instead of approaching teen’s media usage with a “GET OFF YOUR PHONE!!” mindset, let’s talk with teens about why they use technology, in what ways, and how it works and doesn’t work for them. And then let’s empower them to use it in ways that serve them and their “followers.” As Hillary Clinton has said, “Too often, people use [social media] as a weapon instead of an opportunity, and maybe one of the ways we can think together about the next phase of development of social media is as a tool of outreach, a tool of reconciliation, a tool of negotiation, and perhaps a tool of resolution.” And also, I would advocate, as a tool of activism. Social media presents us with an incredible opportunity to be activists within the eating disorders and related fields as well.

Youth in REbeL have started a #PostPositive campaign in which they model body positivity through unfiltered selfies, photos in which they are “doing beautiful,” and #WhiteBoardWednesday, a weekly celebration of sharing their whiteboard photos that challenge the all-too-common practice of body bashing. Through social media, they also fight weight bias, break stereotypes related to body shape and size, and challenge the stigma surrounding eating disorders and other mental health illnesses. These teens recently created a 15-second public service announcement that aired on NBC’s TODAY with the theme of #LoveYourSelfie. This clip was made entirely by youth, from the story concept to the final edits. To view the clip, click here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g0GMc_ep92s

As Sasha Costanza-Chock wrote, “Young people appropriate every new form of media for their own ends, including for social movement purposes.” (Costanza-Chock, 2012). Let’s work with and learn from our youth in this arena and not be afraid of technology and the incredible positive power that social media can have.

Conclusion

Youth get the message that they are not valued, needed or important. But we actually need all that they have to offer. Toffler warns that, for society to try to solve its desperate problems without the full participation of all its members is absurd.

Body hatred, the diet culture, eating disorders, weight stigma, bullying and size discrimination–these are just some of the “desperate problems” facing our society today. And young people want to be part of the solution. Theywant to make a difference and have an impact. They want to help others and have their personal experiences be of benefit. Partnering with young people has significant benefits to the youth themselves, adults with whom they work, and the social causes in which they believe. They are natural activists and we can be their allies. Young people have something to say, and we can learn a lot by listening.

I finally realized that, I’m born with my body—that’s all I have—and that’s all I’m going to have for my entire life from when I’m born until I die. So, I could either spend my time hating myself, which is a waste of time, or I could spend my time loving myself, which is much more constructive and happy. In that, I can find an even stronger love for other people, too.

As Pema Chodron has said, “We don’t set out to save the world; we set out to wonder how other people are doing and to reflect on how our actions affect other people’s hearts.” In the end, isn’t loving ourselves and each other the ultimate form of prevention? And if we change the world along the way, all the better.

REFERENCES:

Chodron, Pema. (2000). When Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice For Difficult Times. Boston: Shambhala.

Costanza-Chock, C. (2012).Youth and Social Movements: Key Lessons for Allies. The Kinder and Braver World Project Research Series, The Born This Way Foundation.

Creighton, A., Kivel, P. (2011) Helping Teens Stop Violence, Build Community and Stand for Justice. Hunter House, Inc. Publishers

Evans, N. J, Forney, D. S. (1998). Student development in college: theory, research, and practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Hillary Clinton Says Social Media Can Help Conflicting Nations “Find Our Humanity”. Retrieved February 21, 2014, from:

Klar, M., & Kasser, T. (2009). Some Benefits of Being an Activist: Measuring Activism and Its Role in Psychological Well-Being. Political Psychology, Volume 30, Issue 5, pages 755–777.

Klindera, K., & Menderweld, J. (2001). Youth Involvement in Prevention Programming. Advocates for Youth.

Levine, M., & Smolak, L. (2006) The Prevention of Eating Problems and Eating Disorders: Theory Research and Practice. Mahway: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Mills, A. & Osborn, B. (2003) Shapesville. Gurze Books

Musick, M. A., & Wilson, J. (2008). Volunteers: a social profile. Bloomington: Indiana University Press

Pittman KJ, Zeldin S. (1995). Premises, Principles, and Practices: Defining the Why, What, and How of Promoting Youth Development through Organizational Practice. Washington, DC: Academy for Educational Development, Center for Youth Development and Policy Research.

Positive Youth Development. Retrieved February 22, 2014 from http://www.findyouthinfo.gov/youth-topics/positive-youth-development

Siegel, D. (2014). Brainstorm: The Power and Purpose of the Teenage Brain. Tarcher, 2014.

Sloane BC, Zimmer CG. The power of peer health education. Journal of American College Health 1993; 41:241-245

Stice, E; Shaw, H. Eating Disorder Prevention Programs: A Meta-Analytic Review, Psychological Bulletin, American Psychological Association, Inc. 2004, Vol. 130, No. 2, 206 –227

Tartakovsky, M. (2012). Ideas for being an eating disorder activist. Retrieved March 22, 2013, from Psych Central:http://blogs.psychcentral.com

Teens’ Time Spent Online Grew 37% Since 2012, Outpacing Other Age Groups. Retrieved February 21, 2014, from: http://www.gfk.com/us/news-and-events/press-room/press-releases/pages/teens-time-spent-online-grew-37-since-2012.aspx

Wheatley, M. (2009) Turning to one another: Simple Conversations to Restore Hope to the Future. Berrett-Koehler.

About the authors:

Carmen Cool, MA, LPC is a psychotherapist in Boulder, CO, specializing in binge eating disorder. Having worked for over 15 years in the field of eating disorders/disordered eating, both in private practice and in treatment centers, she has been moving more into advocacy work. She has run youth programs since 2004, championing them to raise their voice and create new cultural norms around body image, and is a frequent presenter, locally and nationally on Health At Every Size®. She was named “Most Inspiring Individual” in Boulder County, and was the recipient of the Excellence in Eating Disorder Advocacy Award in Washington, DC.

www.carmencool.com

Carmen Cool, MA, LPC is a psychotherapist in Boulder, CO, specializing in binge eating disorder. Having worked for over 15 years in the field of eating disorders/disordered eating, both in private practice and in treatment centers, she has been moving more into advocacy work. She has run youth programs since 2004, championing them to raise their voice and create new cultural norms around body image, and is a frequent presenter, locally and nationally on Health At Every Size®. She was named “Most Inspiring Individual” in Boulder County, and was the recipient of the Excellence in Eating Disorder Advocacy Award in Washington, DC.

www.carmencool.com

Dr. Laura Eickman is a Licensed Psychologist in Kansas. She has worked with individuals with eating disorders in prevention, education, and treatment capacities since her undergraduate years. Laura is committed to increasing prevention efforts in this field; she founded and developed the REbeL Peer Education Program in 2008. REbeL (www.re-bel.org) is a not-for-profit organization on a mission to change the definition of health and beauty for every body. Laura was chosen as one of the Rising Stars of Philanthropy by Nonprofit Connect for her work with REbeL. She also serves on the Board of Directors for the Body Balance Coalition, and provides education and consulting through her company, True North. (www.find-truenorth.com).